گزارش یک مورد نادر: اسپاسم دوطرفه همیفاسیال ناشی از شوانوم دوطرفه عصب صورت

هدف این مطالعه، ارائه یک مورد با اسپاسم دوطرفه همیفاسیال (BHFS) و شوانوم دوطرفه عصب صورت (Facial Nerve Schwannoma – FNS) است. همچنین، تفاوتهای تشخیص شوانوم عصب صورت، تظاهرات بالینی، ارتباط ژنتیکی و ویژگیهای تصویربرداری CT و MRI آنها بررسی میشود.

سابقه:

اسپاسم همی فاسیال (Hemifacial Spasm – HFS) یک نوروپاتی جمجمهای بیشفعال است که باعث انقباضات عضلانی پراکسیسمال در صورت میشود. BHFS یک سندرم عصبی نادر است که تشخیص آن نیازمند حذف سایر اختلالات حرکتی صورت است. شوانوم عصب صورت (FNS) میتواند هر بخشی از عصب صورت (Facial Nerve – FN) را درگیر کند. اسپاسم دوطرفه همی صورت ناشی از FNS دوطرفه، تظاهر بالینی نادری به شمار میآید.

شرح مورد:

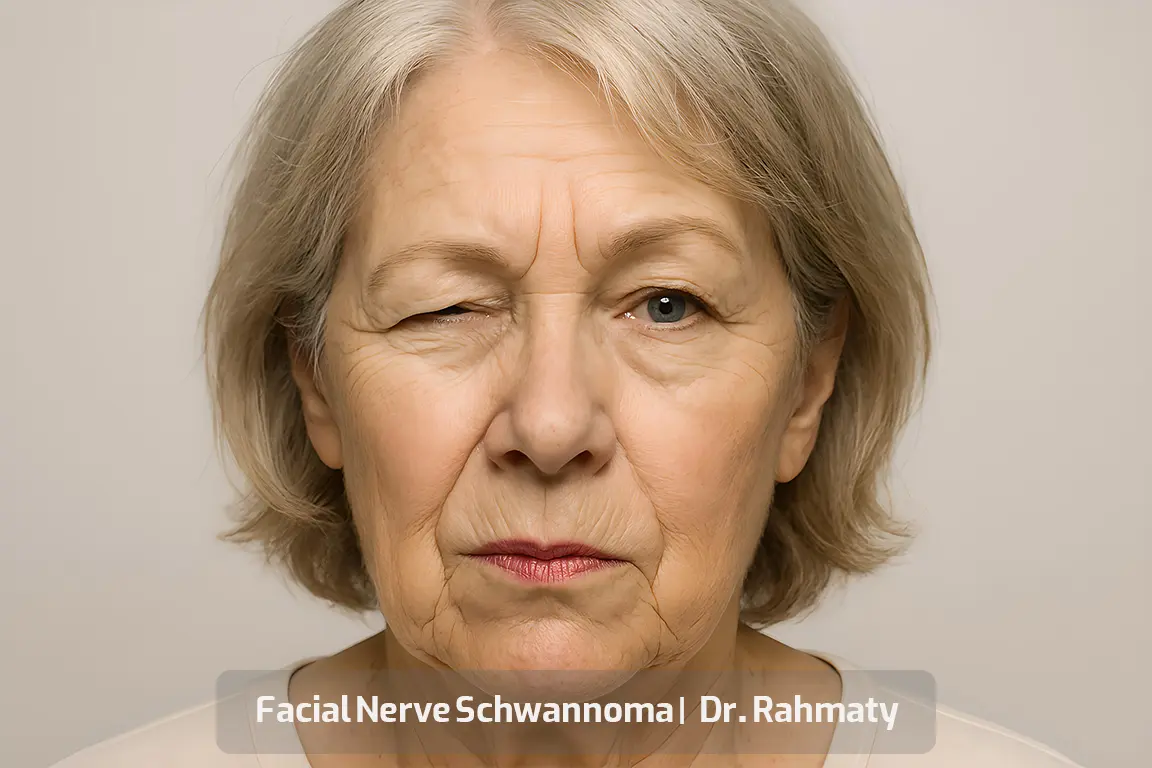

بیمار خانمی ۳۹ ساله با HFS دوطرفه و FNS دوطرفه مراجعه کرد. در سمت راست صورت، درجه دوم اختلال براساس سیستم هاوس-براکمن (House-Brackmann) مشاهده شد. در طول معاینه، تیکهای مداوم صورت در دو طرف دیده میشد، بهویژه اطراف چشم چپ. بیمار تزریق دوطرفه سم بوتولینوم A دریافت کرد و در یک برنامه پیگیری سازماندهی شد.

پیگیریها بر ارزیابی شنوایی، عملکرد عصب صورت و علائم بیمار متمرکز بود. در بازههای ۱ ماهه، ۳ ماهه، ۶ ماهه و یک ساله، بهبود علائم مشاهده شد. پس از یک سال، MRI مجدد انجام گرفت و اندازه ضایعات بدون تغییر نسبت به MRI اولیه باقی مانده بود. تزریقهای بوتولینوم A به صورت دوطرفه هر ۶ ماه یکبار ادامه پیدا کرد و برنامه تصویربرداری سالیانه برای پیگیری تعیین شد.

نتیجهگیری:

اگرچه جراحی یک گزینه مناسب برای برداشتن FNS است، در شرایطی که فلج عصب صورت یا کاهش شنوایی قابل توجه وجود ندارد، درمان علامتی و پیگیری دقیق میتواند بهترین انتخاب باشد.

زمینه شوانوم عصب صورت:

شوانوم عصب صورت (FNS) که به عنوان نورینوما یا نوریلوما عصب صورت نیز شناخته میشود، از سلولهای شوان منشأ میگیرد و میتواند در هر بخشی از مسیر عصب صورت، از زاویه مخچهای-پل (Cerebellopontine – CP angle) تا شاخههای خارججمجمهای در فضای پاروتید ایجاد شود.

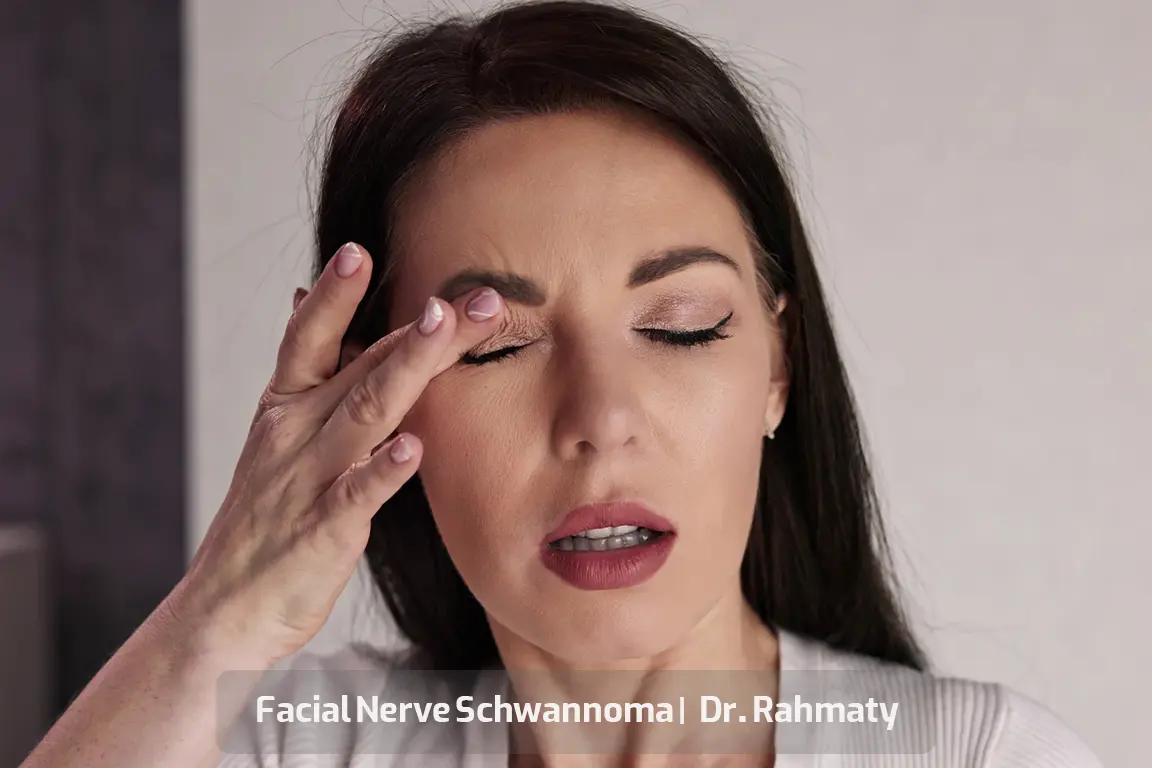

علائم شامل اثر تودهای بر ساختارهای مجاور است که ممکن است منجر به کاهش شنوایی حسی-عصبی، کمشنوایی هدایتی، وجود توده در گوش میانی، یافتههای دهلیزی مانند اسیلوپسی (oscillopsia)، عدم تعادل و بیثباتی وضعیتی و نیز اختلال عملکرد عصب صورت شود. این اختلالات ممکن است شامل فلج بل (Bell’s palsy)، ضعف، انقباضات موضعی یا اسپاسم کامل همی صورت باشد.

در این گزارش، موردی از شوانوم عصب صورت دوطرفه همراه با BHFS و تحلیل یافتههای بالینی و تصویربرداری MR و CT ارائه میشود.

توصیف مورد شوانوم عصب صورت:

بیمار خانم ۳۹ سالهای با حرکات غیرارادی دوطرفه صورت به کلینیک گوش و حلق و بینی مراجعه کرد. علائم او طی ۷ سال به تدریج پیشرفت کرده بود. ابتدا نیمه پایینی سمت راست صورت او درگیر شد و سپس با انقباضات خفیف و ناگهانی به قسمت بالایی گسترش یافت. انقباضات طی ۶ ماه اخیر به ویژه اطراف چشم چپ بارزتر شده بود.

حرکات غیرارادی چند ثانیه طول میکشیدند و در روز حدود ۳۰ تا ۴۰ بار در سمت راست و هفتهای یکبار در سمت چپ تکرار میشدند. بیمار سابقه درمان با سم بوتولینوم به دلیل فلج سمت راست صورت داشت. همچنین از وزوز گوش دوطرفه و گاهی سردرد شکایت داشت اما فاقد علائم دیگری نظیر نقص بینایی یا کاهش شنوایی بود.

در سابقه پزشکی، کبد چرب و هیپرلیپیدمی خفیف وجود داشت. بیمار از داروهایی مانند نورتریپتیلین، کلونازپام، اسیتالوپرام، پروپرانولول و بوسپیرون به دلیل اضطراب و افسردگی استفاده میکرد. هیچ سابقه خانوادگی از نوروفیبروماتوز یا اختلالات ژنتیکی در خانواده وجود نداشت.

معاینه فیزیکی طبیعی بود. چند ماکول رنگدانهای مانند کک و مک روی صورت و تنه مشاهده شد که قطر آنها کمتر از ۵ میلیمتر بود. اختلال عملکرد خفیف عصب صورت طبق سیستم هاوس-براکمن سمت راست صورت ثبت شد. تیکهای صورت در هر دو طرف، بخصوص اطراف چشم چپ دیده میشدند.

معاینه میکروسکوپی هر دو گوش طبیعی بود و ادیومتری تون خالص طبیعی گزارش شد. تشخیص شوانوم دوطرفه صورت با استفاده از یافتههای CT و MRI تأیید شد. بیمار تزریق دوطرفه سم بوتولینوم A دریافت کرد که علائم اسپاسم و سردرد را طی ۲ هفته بهبود داد.

برنامه پیگیری شامل ارزیابی دورهای شنوایی، عملکرد عصب صورت و علائم بیمار بود. MRI مجدد پس از یک سال نشان داد اندازه ضایعه بدون تغییر باقی مانده است. درمان با تزریق بوتولینوم A هر ۶ ماه یکبار و تصویربرداری سالیانه ادامه یافت.

ملاحظات بیشتر:

درگیری شایعترین محل شوانوم در حفره ژنیکوله (Geniculate ganglion) است (۸۳٪)، و پس از آن بخشهای لابیرنتی و تمپانیک عصب صورت (هر دو ۵۴٪). شایعترین تظاهر بالینی، نوروپاتی صورت (۴۲٪) است.

یافتههای تصویربرداری شامل توده لوبولهای با افزایش سیگنال محیطی (علامت هدف) در MRI و تغییرات کیستیک در ضایعات بزرگتر میباشد. در این مطالعه آزمایش ژنتیک برای شناسایی جهشهای NF2 انجام نشد.

همانژیومهای عصب صورت نیز ممکن است علائم مشابه ایجاد کنند، اما الگوهای تصویربرداری متفاوت دارند. کلستئاتومهای مادرزادی دوطرفه نیز میتوانند اعصاب جمجمهای VII و VIII را تحت فشار قرار دهند و علائم مشابه اسپاسم و فلج صورت ایجاد کنند.

درمانهای اسپاسم همی صورت شامل تزریق سم بوتولینوم A و یا جراحی رفع فشار میکروواسکولار (Microvascular Decompression – MVD) است. در مورد حاضر، تزریق دوطرفه بوتاکس با موفقیت علائم بیمار را کنترل کرد.

نتیجهگیری نهایی:

شوانوم عصب صورت یک تومور خوشخیم است که تظاهرات بالینی آن بسته به محل درگیری متفاوت است. اسپاسم همی صورت ممکن است تنها نشانه تومور باشد. با توجه به اینکه بیماران تحمل فلج صورت یا ناشنوایی ناشی از جراحی را ندارند، در برخی موارد درمان علامتی و پیگیری مداوم نسبت به جراحی ارجح است.